Mervyn Bishop blazed a trail behind the lens. He's got a lifetime of stories to tell

Updated a month ago by Jasper Lindell

Under a vast and big blue sky, and standing in the red sand, a grey-suited prime minister pours a fistful of sand into the hands of an elder.

Taken half a century ago, the photograph of Gough Whitlam and Gurindji elder Vincent Lingiari has come to symbolise a turning point in Australian history and the Aboriginal land rights movement.

Mervyn Bishop, who captured the moment on his Hasselblad camera and created the image he would be forever known for, smiles when he remembers that day in August 1975.

The thing is the great symbolic image is a staged moment. And the Department of Aboriginal Affairs didn't even run it in their next magazine. The real ceremony in which Whitlam handed back the title took place in the shade of a shed. Bad light for a photographer.

Bishop conspired with Keith Barlow, the long-serving Women's Weekly staff photographer, to get the pair outside.

"I said to Mr Whitlam, 'Would you care to come outside into the bright blue sky and sun?' He said, 'Very well.' So I led him out about 20 feet away, propped him, so then he'd stay there," Bishop says.

"I said, 'I'll go and get Uncle Vincent Lingiari.' So he had trachoma and his eyesight wasn't so good. And I placed him in this position, deeds in one hand and papers. And I moved his around and set him up.

"You stand like this, Uncle.' 'Yeah, yeah, yeah boy, yeah boy.' And he did. Then Gough bent down and picked up some sand and undertook about four pictures."

After Barlow took his pictures of the curated moment, Bishop's great instinct as a news photographer kicked in.

"Then we went over and said, 'Thank you very much.' And tried to split them up so that no one else could. But other blokes snuck in there," Bishop says.

It's one thing to get the shot. The next thing is always to make sure no one else does.

If it weren't for Whitlam being dismissed as prime minister less than a month later by the governor-general, it might have been the defining image of Whitlam's government.

Bishop, Australia's first Aboriginal press photographer, has directed his lens to countless subjects and worked in the high-pressure environment of daily newspapers. His extensive archive has been reinterpreted and rediscovered, as the impact of a Black photographer came to be understood.

Born in Brewarrina in 1945, Bishop borrowed his mother's Kodak Brownie about the time of his 11th birthday.

Aged 12, Bishop bought an Acon rangefinder that took 35-millimetre film for 15 pounds - the equivalent of about two or three weeks' wages for some adults at the time - after saving money from mowing lawns and collecting deposits on bottles.

The camera allowed Bishop to take Kodachrome slides, vivid colour positive film which, after processing, can be projected. Bishop's family would borrow a slide projector and have a look at the photographs Bishop was taking.

"Maybe every fortnight, you might get a new packet of slides back from Melbourne, and put a sheet up on the clothes line - peg it out so it's nice and flat. ... One slide in, take that one out, change, make sure it's the right way. ... I just love the mechanics of it," Bishop says.

At 17, Bishop landed a job as a cadet photographer on The Sydney Morning Herald. It would be the start of a long and varied career, with triumphs and disappointments - and an archive far beyond that iconic, staged moment at Wattie Creek.

An hour with Bishop makes two things very clear: the man has stories, and he likes a chat.

Tim Dobbyn clearly learned this too when he went on a road trip through NSW and back to Brewarrina with Bishop as he worked on a biography of the photographer, Black, White + Colour (Ginninderra Press, $59.99). "The road trip was fantastic. And, yeah, lots of diversions, lots of people. And then we talked every week for at least an hour for the next couple of years. And even after the book's over, we still talk to each other every week," Dobbyn says.

"Merv was sort of more my parents' friend when I was growing up. I mean, he was a fun guy to have around, but he's just that bit older. And that makes a big difference when you're younger. Now we're strong mates."

Bishop cuts in. "Brothers," he says.

The biography is an affectionate, warm-hearted portrait of Bishop, who never loses his cheeky side. The connection between Bishop and Dobbyn stretches back six decades.

Dobbyn's father, a sub-editor on The Sydney Morning Herald, had, at the suggestion of his mother, arranged to collect some money each week to help the education of an Aboriginal child. Bishop was one, and he wrote to the sub-editors to thank them for their help, which led to him meeting the Dobbyn family in Dubbo, where he went to boarding school.

Bishop moved to Sydney in 1963, aged 17, for a job as a "general dogsbody" at the ABC. After three disillusioning months in the "paper-and-string job", Dobbyn's father, Alan, helped Bishop get an interview with the Herald's acting photographic manager.

Nights spent in Vic King's darkroom in Brewarrina meant Bishop was no stranger to the task. His slides on the light box had been deemed quite good, and his ability to make a print marked him as proficient. Bishop was offered a cadetship a few weeks later.

A photographer's work on a newspaper is a varied lot. It might be a series of news jobs, or something for the sports pages. Social events and features need photographic illustration, too. In the 1960s, Bishop photographed Roy Orbison, Mick Jagger, Barry Humphries and even Cecil Beaton, the famous British photographer.

Dobbyn's biography details Bishop's experiences of racism in Sydney were often worse than what he'd experienced growing up and at school. City life had different challenges.

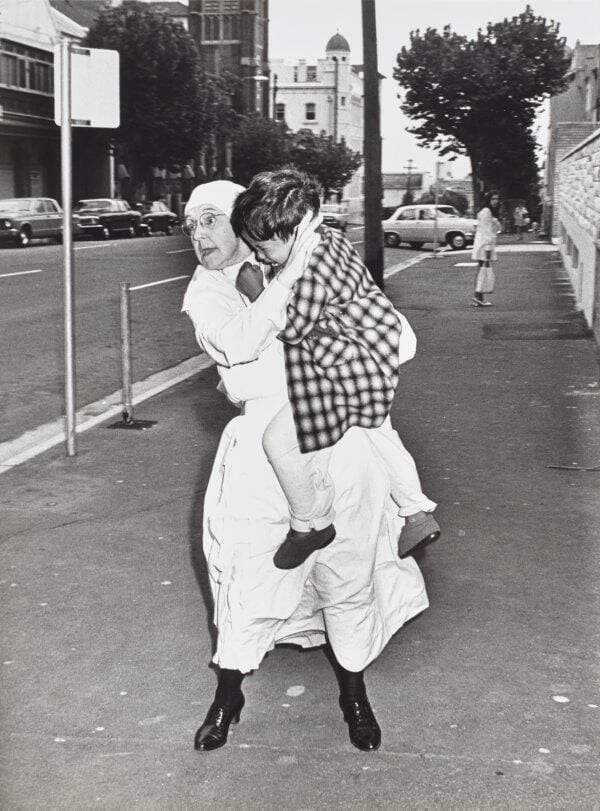

In 1971, Bishop won Press Photographer of the Year for Life and Death Dash, a photograph of a young boy in the arms of a nun being rushed into St Margaret's Hospital in Darlinghurst.

The life of that photograph reveals much about Bishop's career and how his photography is seen.

Bishop and the police reporter on the Sun, the afternoon Fairfax paper, had heard over their car radio that a woman was driving under police escort towards the hospital because her children had accidentally got into her pills. At the hospital, the nun picked up the boy and put up her arm "as if to say, 'Go away, really go away'."

"And I'm just like, click, took one picture. And I took another one, winded on, didn't have a drive. ... And I said, well, I said, I hope you're all right. You know, really, the mother kind of said, 'Thank you.' You know, I said, 'Don't worry about me'. I said, 'Get your kids out into the hospital.' ... I was worried about them. You don't know what sort of pills they were."

The kids were fine. Bishop had a "cracking picture". But what happened next changed the course of his career.

Most winners of top photojournalism prizes stood to be promoted. Not Bishop. "Not a nothing. ... There was a thing going on with the photographic editor or photographic manager," he says.

"He either just didn't like me or whether it was racist, I don't know. ... At the time, my wife said, 'Oh, he's bloody racist. You've achieved and you're a top man in Australia, not just the paper.'

"Other photographers were coming in and they were jumping up ahead of me. Ah, OK. What the? So Aboriginal Affairs started to loom up."

Bishop's decision to move to Canberra and take up a position as a photographer in the Department of Aboriginal Affairs would put him in a position to take his key photograph of Whitlam and Lingiari in August 1975.

The Art Gallery of NSW's website says composition, contrast and Aboriginal social commentary combine in Life and Death Dash.

"It is a classic example of photojournalism that has since transgressed its original context and come to insinuate the impact of religious missions within Aboriginal Australia and, in particular, on the Stolen Generations," the gallery's description of the photograph says.

Dobbyn's biography notes Bishop's attempts to oppose this view of the image have been met with limited success. "There was only one Blackfella there that day and he was behind the camera. ... It was just a bloody good news photo," Bishop says in Dobbyn's book.

And the boy in the photograph? His father had Italian heritage, and his mother was English.

"And years later, there was an exhibition not far from St Margaret's Hospital ... And it must have got word out that I'd be there. But he was at St Vincent's. He was an ear, nose and throat specialist. So he came in with a couple of his doctor mates," Bishop says of the boy he photographed.

"And he said, 'That picture you really took of me', he said, 'Mum has still got the little dressing gown hanging up in the wardrobe.' And she, his mother, took sort of an interest in me, in my years of photography.

"And he said, 'I feel I know you.' Yeah."

News photography has its own edge: a documentary style, clear composition, nothing too ambiguous. The recognition in the art world that came later for Bishop's work, in Dobbyn's telling, could sit apart from the documentary, realist style Bishop has always practised. Equally, the recognition from First Nations artists and photographers for Bishop's work has kept his photographs in people's minds and out of the archives.

Now that he's 80, how does Bishop want to be remembered as a photographer?

"Gee, that's a..." he says, trailing off. "My images, I guess, speak for themselves."

Photographers, Bishop says, if they lay out a stack of images, maybe some of the guys could tell who took what picture without a name on it, as if to say having a style other photographers appreciate and can recognise is the best way to be remembered. A peer review is the only review that matters.

"I particularly like to do portraits of people. Making them feel at ease. Sometimes they didn't want to. 'Oh, but I look terrible' or 'I don't feel so good today'. And I try and change the tone of our conversation," Bishop says.

Ultimately, Bishop is interested in people. In talking to them, meeting them, having a good, long yarn with them. Living in Dubbo, he doesn't pick up the camera as much these days, but that essential skill of being chatty and good company has never left him.

"I've felt mistreated at times by both Whitefellas and Blackfellas, but I love yarning with all sorts of people, and I've kept my politics to myself and played things right down the middle," Bishop writes in the foreword of his biography.

"My images are my message."